Online payment processing and chargebacks have a complicated history. It’s a legacy system that, while modern, took many twists and turns throughout the years.

But whether you run an online store, work for a payment gateway, financial institution or part of a risk operations team, it helps to understand how we got there.

Fraud and Money: a Story as Old as Time

Back in 300 BC, a Greek merchant named Hegestratos decided to insure his ship and cargo. The policy, known as a bottomry, worked on simple terms: Hegestratos could borrow the equivalent of the value of his ship and cargo. If he made it safely to his destination, the loan would be paid back with interest.

If not, the boat and cargo would be repossessed. But Hegestratos had another idea: what if he disappeared? He could sink his empty ship, covertly sell the cargo, and keep the loan for himself. Who knows what would have happened had he succeeded.

His plan backfired when he was caught red-handed by the crew. They chased him off the ship, and Hegestratos drowned in the Aegean sea. This is the first known example in the history of fraud.

It will by no means be the last. As long as money and credit exist, unscrupulous individuals will attempt to game the system.

In this ebook, we’ll look at the history of payments, chargebacks and online fraud, all in an effort to help us see where we might be headed.

Money, Currency and Credit: Basic Definitions

Money is defined as a portable form of property that is used and accepted as a means of exchange. Currency, like US dollars, euros or British pounds is one of those standardized properties.

Credit is borrowed money. It generates debt, which must be repaid, usually with an interest, at a later date.

Credit, Trust and Risk

In Latin, the term “credit” can be translated as “he/she believes”. It implies trust between the borrowing and lending parties.

Unfortunately, it also implies risk. The lender may never recover their loan. The borrower may default on it. Or simply attempt to defraud the lender, as seen in our opening example.

In the era of credit cards, there must also be trust between the cardholder and the merchant where a purchase is made.

So Why Credit Cards, Anyway?

In early Babylon, seeds were sold to farmers so that they could pay back after the harvest, with a small interest. The same principles apply today with credit cards. They exist so banks can make a profit, and so that consumers may increase their purchasing power immediately. It’s also a boon for businesses, who can process more payments.

The Long and Winding History of Card Payments and Fraud

For every innovation linked to credit, there have been fraudulent attempts. For every fraud attack, there’s been a solution. It’s a never-ending cycle that continues well into the modern age. Let’s see how we got there.

The first credit cards may be traced back to the 1940s when air travel companies allowed customers to purchase tickets on credit. By 1950, the Diner’s Club card made its way in American households, allowing people to pay on credit at several retailers.

The sum had to be paid back each month in full. American Express (or BankAmericard at the time), innovated on the same concept in 1958 by offering customers the option to carry the balance on their cards. The modern credit card as we know it was finally born… but it was not without its challenges.

The earliest credit cards were built of metal, so merchants could create an imprint. They filed the information using a non-electronic imprinter, which copied details on a paper receipt. It included the cardholder’s name, expiration date, and of course, the card number. (Fun fact: if the letters and digits on your card are embossed, it’s precisely for that purpose. it is increasingly rare these days).

The cardholder was also required to sign the receipt, which needed to match the signature on the back of their card, for authentication purposes. Unfortunately, stealing a card and pretending to be the cardholder was child’s play for early card fraudsters. The payment verification took days. Forging signatures was easy.

This created a complete lack of trust from the general public. How could they ensure that the credit card was only legitimately used by them, and not a thief? How could they trust that merchants wouldn’t add extra fees after the checkout process? It was time for innovation.

In the late 60s, IBM introduced a new technology that allowed information to be encoded on a magnetic strip. It could be read with specialized computer equipment, and banks loved them, for a good reason: the time to confirm a transaction dropped from multiple days to a matter of seconds.

There were, however, still security issues. The information on these strips was not encrypted. Unscrupulous merchants could steal it after the customer had left. Worse: it didn’t help with the sneaky suspicion that banks were giving you money with a catch.

This is why, in 1968, the US Federal Reserve Board passed the Truth in Lending Act, which required the lender to provide clear loan cost information, including the annual percentage rate (APR), terms of the loan, and total costs to the borrower.

A few years later, in 1974, the Fair Credit Billing Act introduced another reassuring idea: if consumers noticed a suspicious transaction on their credit card bill, they could contest it. Under the act, the consumer had 60 days to dispute a charge with the card issuer. Charges on lost or stolen cards could also be contested. Disputes with merchants could also be settled by requesting their money back – thus the chargeback was born.

It clearly created two incentives: customers would feel more confident paying with a card. And merchants would have good reasons not to try to scam anyone. And while there was an updated Electronic Fund Transfer Act in 1978, the process would remain largely unchanged for nearly forty years.

What Is Chargeback Law?

In 1974, the Fair Credit Billing Act decreed that consumers who noticed a suspicious credit card transaction could contest it with their bank. The goal was to boost trust in the credit card system and to de-incentivize merchants to commit fraud.

Fraudsters were quick to adapt to magnetic stripe technology in the 80s. Credit card cloners became widely available, allowing them to swipe a card at a point of sale, and to copy the information to a blank card.

This stemmed from one key problem: the lack of data encryption between the card, point of sale, and the card network. This is why, in 1993, Europay, Mastercard and Visa, the three biggest card network operators of the era, launched a new technological innovation: EMV chips. (And yes, EMV stands for Europay, Mastercard and Visa. While Europay was later assimilated by Mastercard, the term remains in use to this day.)

The key benefit of adding EMV chips to cards? Information encryption, and two-way authentication between the card terminal and the payment processing network. The goal was to reduce transaction fraud risk. For European merchants, it eliminated the need for expensive phone authorizations. And of course, adding a PIN number to the card also boosted its security.

The chips encrypt the data every time the card is used, and signature verification becomes obsolete. And it seemed to work. While the rollout was slow (especially in the US), EMV technology is said to have helped reduce card-present rate fraud by 87% in the US.

For merchants who failed to upgrade to the latest EMV-reading technology, credit card networks had another surprise in store. They decided to shift liability for counterfeit card fraud losses onto them.

In short, if a card payment is fraudulent, the merchant is now considered the weakest point of the transaction. They are the ones who have to cover the admin fees associated with a chargeback request.

This will have drastic consequences for all companies that accept payments online.

Online stores really took off during the mid-90s, leading to the famous dot com bubble. The companies that survived or grew after it are now household names: Amazon, eBay, Etsy, Shopify… Part of the success of these online stores is their ability to support multiple options.

Since 2001, PayPal promised to change how online payment processing worked and became the default payment method for millions of eBay users. Yahoo’s PayDirect and GoogleCheckout proved less successful, but nevertheless paved the way for modern online payment channels.

In 2010, eBay’s co-founders Elon Musk and Peter Thiel also invested in the payment processing software company Stripe, which is now valued at $95B. In spite of their popularity, all these online payment companies still face the same problems as card networks: how to improve security and reduce fraud.

Other noteworthy developments during that period include the founding of the 2004 Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council (PCI), designed to standardize security requirements for online payments. A few years later, Visa also developed 3D Secure, which helps authenticate users before payments.

Unfortunately, these security measures tend to add friction to the user checkout experience – something mobile payments are now attempting to bypass today.

In fact, user authentication for payments will become the next battleground for fraudsters and financial institutions.

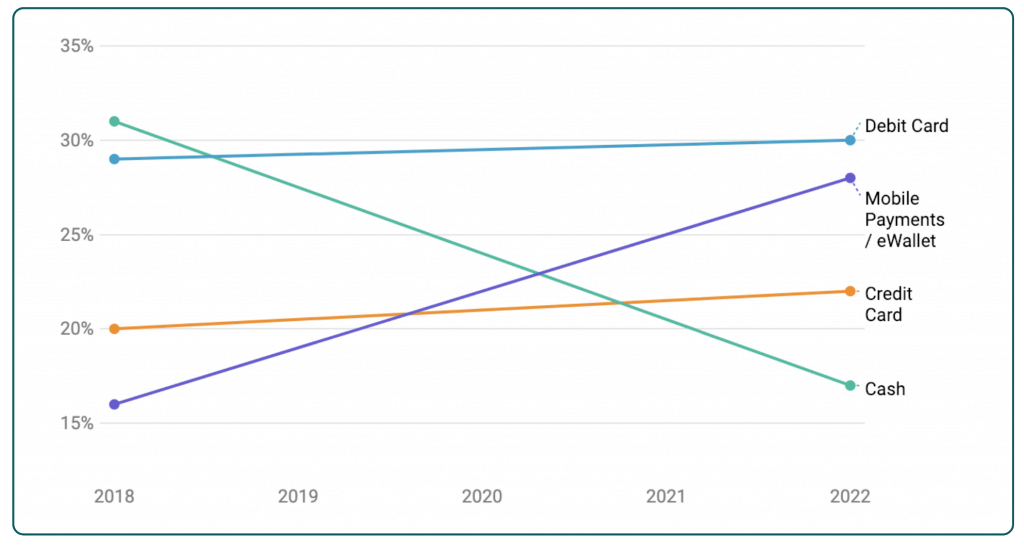

While credit card usage is steadily increasing worldwide, it pales in comparison with the unstoppable rise of mobile and eWallet payments. This is what online payment processing looks like in chart form today, according to data from WorldPay’s global payments report of 2021.

Source: https://www.merchantsavvy.co.uk/mobile-payment-stats-trends/

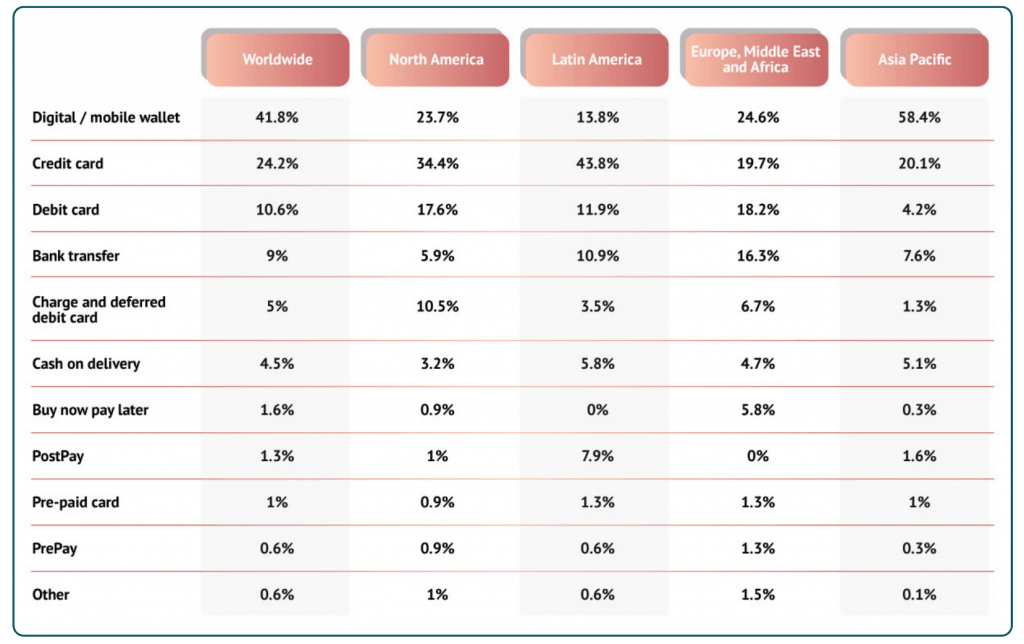

Ewallets have officially been available since 2008. Their usage has shattered all expectations, especially in regions like China and the APAC region. Rapid digitization following the COVID-19 pandemic has also accelerated adoption.

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/348004/payment-method-usage-worldwide/

Well, there have still been a few interesting developments since the mid-2010s. The most noteworthy is undoubtedly the VCR, or Visa Claims Resolution, launched in 2017. (Mastercard implemented its own dispute resolution initiative the same year).

To explain it succinctly, fraudsters had now moved from a card-present scenario to card-not-present (CNP) fraud. While EMV technology had helped curb in-person card fraud, it did little to stop fraud online or over the phone.

This created yet another huge headache for card networks and merchants. Chargeback rates, to this day, are still way too high in CNP scenarios.

And resolving them is expensive, time-consuming, and frustrating partly due to the complexity of the modern online payment ecosystem.

How Does Online Payment Processing Work?

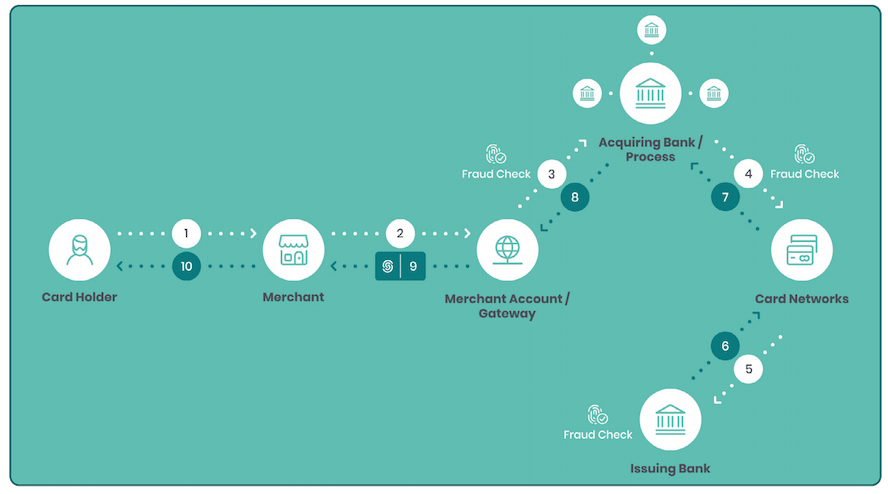

One of the reasons chargebacks are so complex? They can involve several parties. This is what modern online payment processing looks like today:

Now when a chargeback is initiated by the cardholder, the process also has to be acknowledged by multiple parties.

- The cardholder initiates the chargeback request.

- The issuing bank sends the request to the acquiring bank.

- The acquiring bank sends the request to the merchant.

- The merchant can accept the charge, or dispute it.

Then, there are three potential scenarios:

- The merchant accepts the charge and loses the funds, plus a fee.

- They dispute it and lose their appeal (same as 1).

- They dispute the chargeback and win.

The dispute process, it should be noted, is in no way straightforward. It is time-consuming. It may take weeks, requires extensive knowledge of chargeback codes (for specific reasons), and there can be a second chargeback or pre/arbitration stage. Risk teams can lose hours with one single dispute, which is why many merchants opt for simply dealing with the loss rather than wasting energy fighting the chargeback.

Credit Card Fraud: a Quick Primer

The first thing to understand is that the term credit card fraud includes acts committed with any payment card. That means credit cards or debit cards. Then, there are roughly two types of setups:

- Card Present Fraud: when the card has been physically stolen, altered or manipulated to defraud the account linked to it. The card is also physically presented to the merchant, offline.

- CNP – Card Not Present fraud: where only the credit card information is given to pay. This can be online or over the phone, for instance.

One of the most popular terms for CNP fraud is called Carding, where fraudsters acquire other people’s credit card numbers (usually on a darknet marketplace) and use them to purchase goods or services online or in-store. Another strong contender: friendly fraud, also known as family fraud or chargeback fraud. This is a chargeback request initiated by a cardholder, who is either:

- Innocent: They genuinely forgot about the purchase, or a family member paid for an item without their authorisation (i.e. children buying in-app DLC…)

- Opportunistic: A dissatisfied customer wishes to punish the vendor to protest a policy or to damage their business.

- Malicious: When the cardholder buys an item with their card, and every intention to pretend that they didn’t.

Friendly fraud is growing at an alarming rate, and it’s a real challenge to solve for online merchants. They don’t just have to prove that the purchase exists, but also justify the user intent, usually by providing lengthy reports on their shopping history. Complicating the matter, some merchants may also be fraudulent. They may:

- Be complicit in processing payments from stolen card numbers.

- Attempt to pass as less risky than they really are in terms of chargeback rates.

A note on that latter point: because banks want to reduce chargebacks costs, they may increase the fee they take on transactions with high-risk merchants. So an online store that sells expensive software, for instance, may have to pay more to allow card payments. Other known high-risk stores include electronics, iGaming and gambling sites, adult material, SEO services, vitamins and supplements, and many more…

Unfortunately, this is a strong incentive for the less scrupulous merchants to hide what they really sell, so they can process card payments cheaper by hiding their chargeback history.

A Note on Cryptocurrencies

Cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ether could, in theory, eliminate chargebacks altogether. Transactions made with crypto are much more akin to cash-based exchanges: they come from a decentralized issuer, and they are irreversible.

Where things become more complicated, however, is that crypto exchanges may accept payments via credit card. In that case, the problem of chargebacks still exists, and the exchange becomes another merchant: they are the ones liable to return the money to the buyer or to dispute the chargeback.

In fact, because of their use by fraudsters and criminals, crypto fraud is rampant. Exchanges are a high target and have some of the highest chargeback rates of all businesses.

To make matters worse, the volatile nature of some crypto assets means that unsatisfied customers will often hit exchanges with a chargeback request to recover their losses.

Volatility could also be to blame for the relatively slow adoption of crypto by merchants. While a new wave of so-called stablecoins (pegged to other real-world currencies) aims to solve the problem, many companies still prefer taking card payments at the risk of losing a certain percentage to chargeback fees.

Every Company Must Be a Fintech Company

You may have heard the aforementioned statement, and it holds truer than ever today. Analysts claim that COVID-19 has accelerated digital transformation by a few years, and businesses that have yet to operate online are a rare breed these days.

The issue, of course, is that accepting payments online is easy to do, but hard to do securely. In a card non-present scenario, you are always at the mercy of fraudsters, whose sophistication and agility never cease to amaze.

The key to growing your business safely online? Understand where risk exists. Learn who the enemy is. And deploy the right fraud prevention service to protect your company. Hopefully, SEON and this ebook can help with all three points.

You might also be interested in reading about:

- SEON: Ecommerce Fraud Detection & Prevention

- SEON: Payment Fraud Prevention & Detection

- SEON: How to Fight Return Fraud

- SEON: Best Fraud Prevention & Detection Software

Learn more about: Data Enrichment | Browser Fingerprinting | Device Fingerprinting | Fraud Detection API